This is the full speech of my talk on the relationship between the creative works we make and the world we live in.

Some quick background:

I was invited to give a talk at the Sweden Games Conference this year (2018). I felt relief when I saw the topic of the conference: “Politics & Games: Reflections on Power, Play, & Changing Perspectives”. It meant I could talk about anything. I mean, we all can anyway. But I knew there would be a (potentially) more welcoming audience.

What I share in this talk is a viewpoint I’ve been coming to for a while now. Specifically, the concepts started with my talk at ANZCA in July last year (2017) with my talk “Comparing World Recentering Practices in Australia and the USA”. In that talk I was trying to reconcile my intuition about my attraction to pervasive media practices as compared to immersion as transportation. Another key development of the worldview concept was in June this year (2018), with my blog post “The Two Markets: Finding Your Kin”. Then I stumbled on a book and all the concepts fell into place.

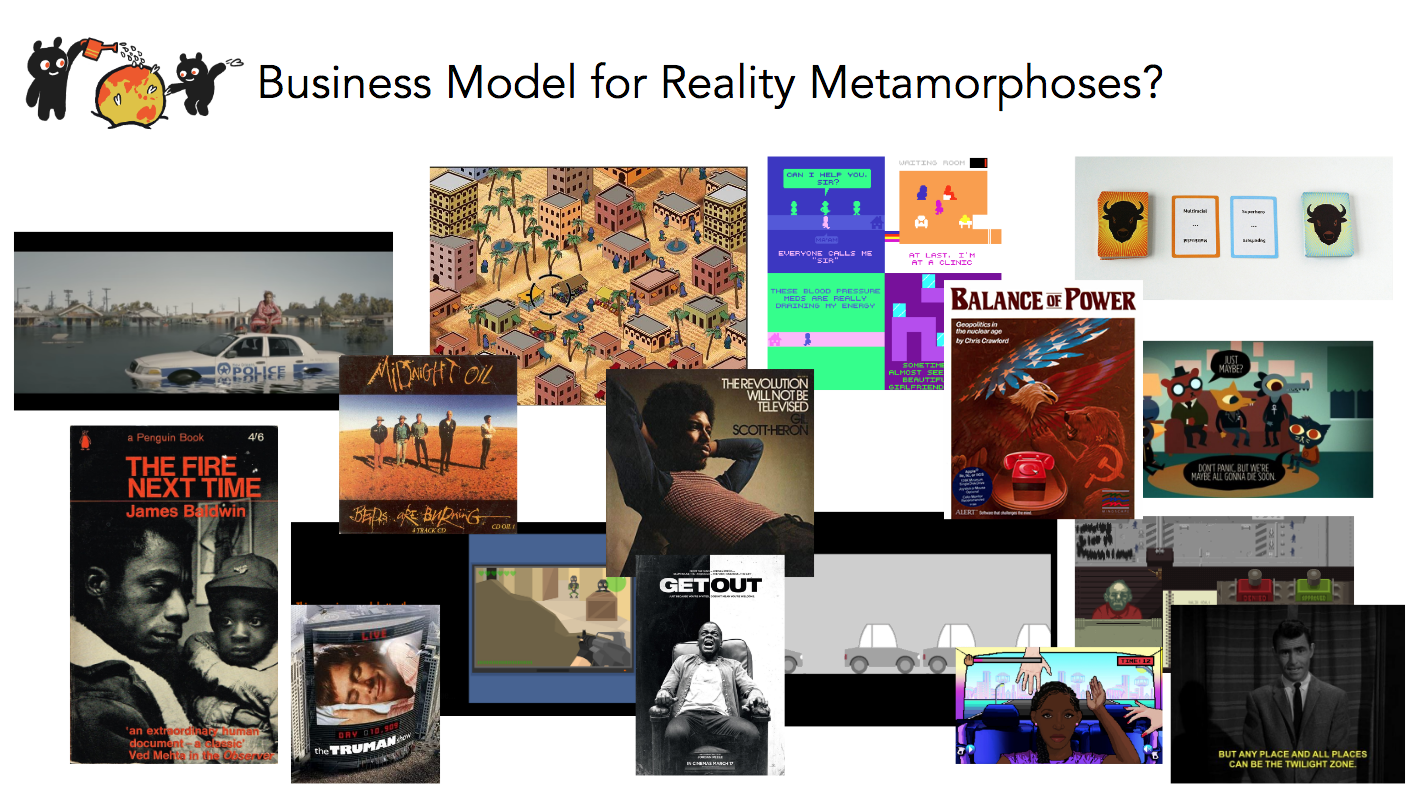

So here is the speech. I include both game and non-game examples. In my last talk for GDC, I gave mainly game examples only. While that was helpful, some people didn’t see how the concepts are transdisciplinary. So this time I included a range of examples.

There will be some small differences with the video, as I couldn’t always read the text on my screen (ha!) and of course I improvised. I took out a few slides to fit the time, which aren’t here either. A couple I want to highlight are 1) more descriptions on the theory and how it works; 2) the role of dystopia and how it has a limited role in facilitating change. But all this will be developed further with the academic paper I’m writing on this, and of course for my book. So let me know your thoughts – whatever they are – as that will help with my further writing on this topic!

So here is the video of the talk, and the original speech. The video includes a Q&A, in which I do the really weird thing of not letting people know that my book includes tips on how to then action these insights! I have been touring my concepts and not wanting to tease people with the book when it may be a while before it releases. But I forgot I’m now closer to releasing it. My talks and workshops are all from the book. Indeed, “Worldbuilding our World” is at present the working title. And the art is from the book, by my wonderful collaborator Marigold Bartlett.

Anyway – over to you to check out something that has helped me understand my practice immensely, and hopefully yours too. [And also check out all the amazing collection of talks from the conference!]

Video of talk:

Original speech:

[content warning – mention of some hate crimes, but I avoid going into detail, and I refer obliquely to projects but don‘t name or show them.]

Hello everybody! I’m going to get straight into what I want to share with you. I want to take advantage of my time in this talk, and my time on Earth, I want to use my time wisely (which to me also means enjoying it)! So straight up: I decided in my teens that it was through creative projects that I wanted to change the world. I did consider law for a bit, but it was creative practice that was my calling and my choice. So when I look at worldbuilding techniques, it isn’t to see how I can create an immersive world to transport you to for a few hours. No, it is to see if there is a glimpse into how new worlds are made.

This is one of my ongoing life clipboard questions. Do you have life clipboards? It is virtual clipboard of questions that I have about life. Some of them take hours or weeks to answer, but most of them take years. Here are some of the current questions I’ve been looking at in my life:

1) Why is it I don’t find many AAA, double AA and Hollywood studios appealing to work in, despite the great talent and resources? 2) How can I help others understand why I turn down working with some great clients and companies? 3) Do you really have to make one kind of project for a mass market? 4) What other ways can the core essence of a creative project be understood? (Transmedia) 5) Do I, and others, do harm with the projects we create? 6) Can creative projects really change the world? 7) Can I, can you, change the world, now? All of these questions have the same answer. It’s a broad spectrum solution or insight, that works for me. I am sharing it here today, in case any of these thoughts help you with your own questions (some of which may be the same). And in order to do this, I need to go back to a book that was published in 1966.

The book was written through a collaboration of American-Austrian’s Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann. The images here are of Peter Berger, who has spoken about his long-term curiosity with ‘what makes people tick’ (same here!). In a documentary, he talks about an early memory he has of being given a toy train. But he didn’t switch on the electricity to see it turn around the tracks. Instead, he lay on his belly and talked to the imaginary people on the train. The book I’m going to talk about today is the result of this curiosity. People have gone up to Berger that after reading the book and tell him how they see the world differently, and he said he understood because he too saw the world differently once the ideas became clear to him. So let me share with you what it is about (and some of you will know it anyway).

The book is “The Social Construction of Reality”, and it is considered one of the top influential sociology books of all time. When it was published in 1966, world events included the death of civil rights activist Vernon Dahmer in Mississippi, and a Ku Klux Klan member is unsuccessfully tried for his murder 4 times; Indira Ghandi is elected the first and to-date only female Prime Minister of India; and the first Winnie the Pooh feature film is released. In the academic context, Berger (I will refer to Berger as the shorthand for Berger & Luckmann from now on, and I have changed the pronouns in quotes,and I use the American spelling from the book – FYI). Berger’s book contributed to what is called “the sociology of knowledge”. Previously, all questions of the nature of reality were discussed through the theories of philosophers and scientists for instance. What Berger’s book argued was that we need to look all forms of knowledge not just knowledge from “great thinkers”. We all construct knowledge they argued, and so we should look at what passes as “common-sense knowledge”. How is it that we construct our reality?

Firstly, let’s define the amazing notion of “reality” really quickly. To Berger, “reality is a quality appertaining to phenomena that we recognize as having a being independent of our own volition” “we can’t wish it away”. It’s reality.

So how is reality socially constructed? And is it possible for us to discuss this AFTER the big party last night? We will find out! First…

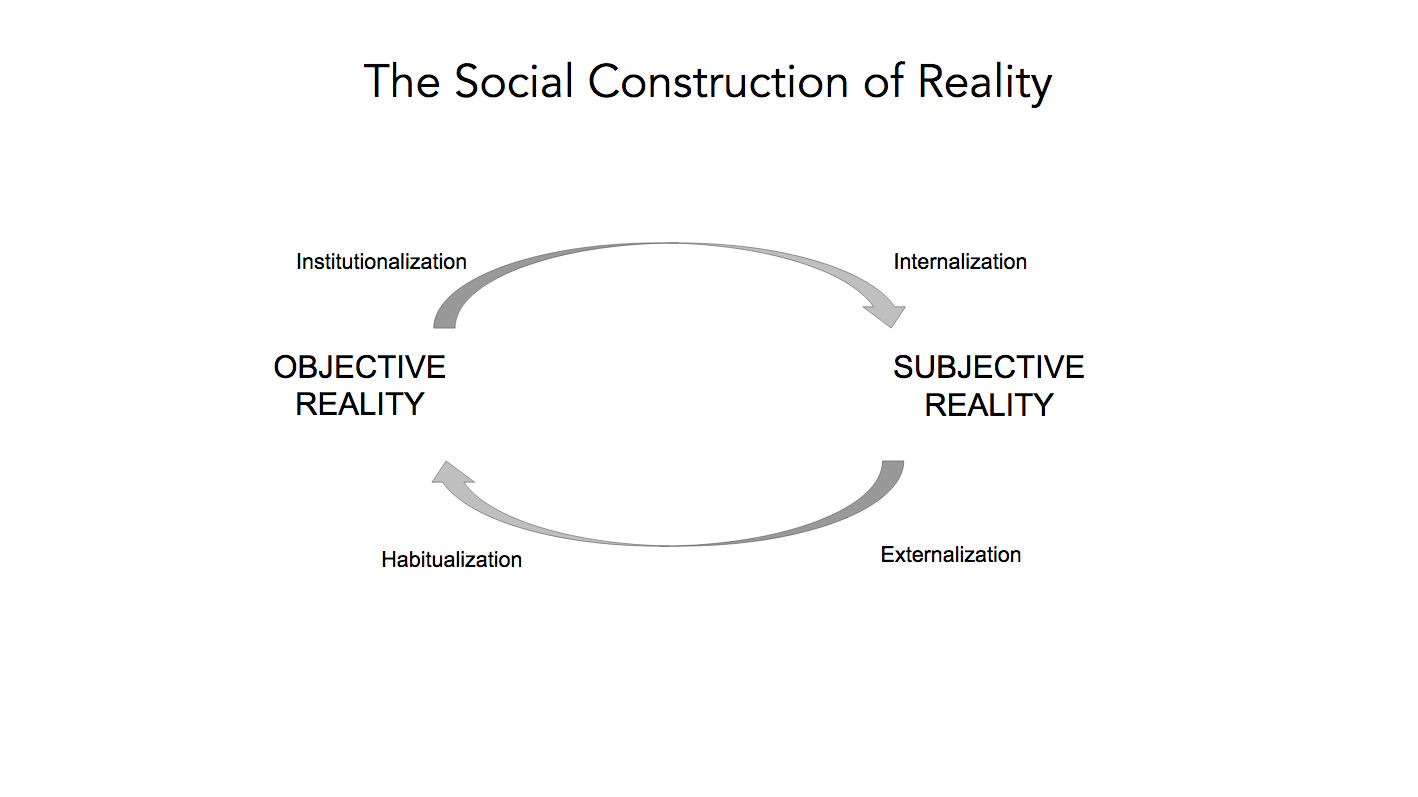

Reality is co-constructed — we all create our human environment, with everything we say and do. Berger calls them our externalisations.

As creatives, externalization is a term to describe any activity that gets our ideas out of our head. It is a music score, a sketch, a storyboard, a diagram, a script. This process is essential to not just understand what the project is through the act of creation, but to communicate it to others. Indeed, a creation is an act of communication. Communication with the self, and communication with others. But externalization also includes any time we talk, any time we write, we write a law, we write a course, we write code, any time we make sound, we make a gesture, we externalise our inner world. These externalisations are our human activities. They’re what we do in the world.

Over time, our activities become habits. When we repeat them often enough, they become a pattern (a schema in our mind). That is, rather than remembering every little step and every possible action we could do in each moment, we end up remembering only what we’ve been repeating. We don’t remember the different ways we could do something, we remember the way we end up doing something repeatedly. And then that becomes automatic. A musician, for instance, develops muscle memory with their guitar. And we always greet someone when we meet but we often don’t actually listen to what we’re actually saying to each other. This brings us the important psychological benefits of habits – they narrow choice so we don‘t have to expend as much cognitive effort, we are freed from the burden of ‘all those decisions’. Our activities become routines, we create a stable environment in which we do a minimum of decision-making. Our actions become automatic, unconscious, and we forget we had choices.

These habits, over time, become institutions. Now, you may be thinking, like I did, of an institution, like a building. How can a habit become a building?

But for our sociologists, an “institution” describes the types of actions performed by types of people. Employers issue work duties, and employees execute them. There is the institution of marriage where you have celebrants who conduct a wedding ceremony for instance, institution of law, of education, and the family. Institutions aren’t created instantaneously, remember the habits – it needs to happen over time. Interestingly, institutions are about “controlling human conduct by setting up predefined patterns of conduct, which channel it in one direction as against the many other directions that would theoretically be possible”. Institutions define what control is exerted, by whom, how, and with whom.

The transmission of institutions also happens through parents. They tell their children stories, they read storybooks about the institution of marriage (that girls and boys want to marry, and there are social rules around who can marry who). As Berger explains, “since the child had no part in shaping (this reality), it confronts them as a given reality.” Indeed, “all institutions appear in the same way, as given, unalterable and self-evident.” An institution doesn’t occur unless it is passed on through a generation, otherwise it has failed.

In our parents stories, in the everyday comments to each other, in our films, in our games a reality takes shape, and is presented to us “as undeniable facts. The institutions are there, external to us, persistent in their reality, whether we like it or not”. It takes on an objective nature because it is persistent and echoed everywhere. And we forget we have a choice, we forget we made it. So we have our externalisations that share our inner world, we develop habits, these unconscious habits become institutions, and we‘re surrounded by them.

What happens over time is what is called “Reification” – this is, we think that what we create is something generated by anything but our ourselves, and certainly not generated by the everyday. Over the generations, we forget why certain social order was put into place, and then we forget we put it into place ourselves. “Human meanings,” Berger explains, “ are no longer understood as world-producing but as being products of the ‘nature of things’.” Our roles too can become reified. A role, such as being a husband, wife, girlfriend, boyfriend, employee, and manager, can be “apprehended as an inevitable fate, for which the individual can disclaim responsibility.” This is when we say “I have no choice in the matter, I have to act this way because of my position”. I have to fire those people for being uncivil, because that is my role and that is the logic of the economic institution. Indeed, you can assume a total identification with your social assigned type and see it as something outside of your control. You are a boss, you are a geek, you are meant to be hot.

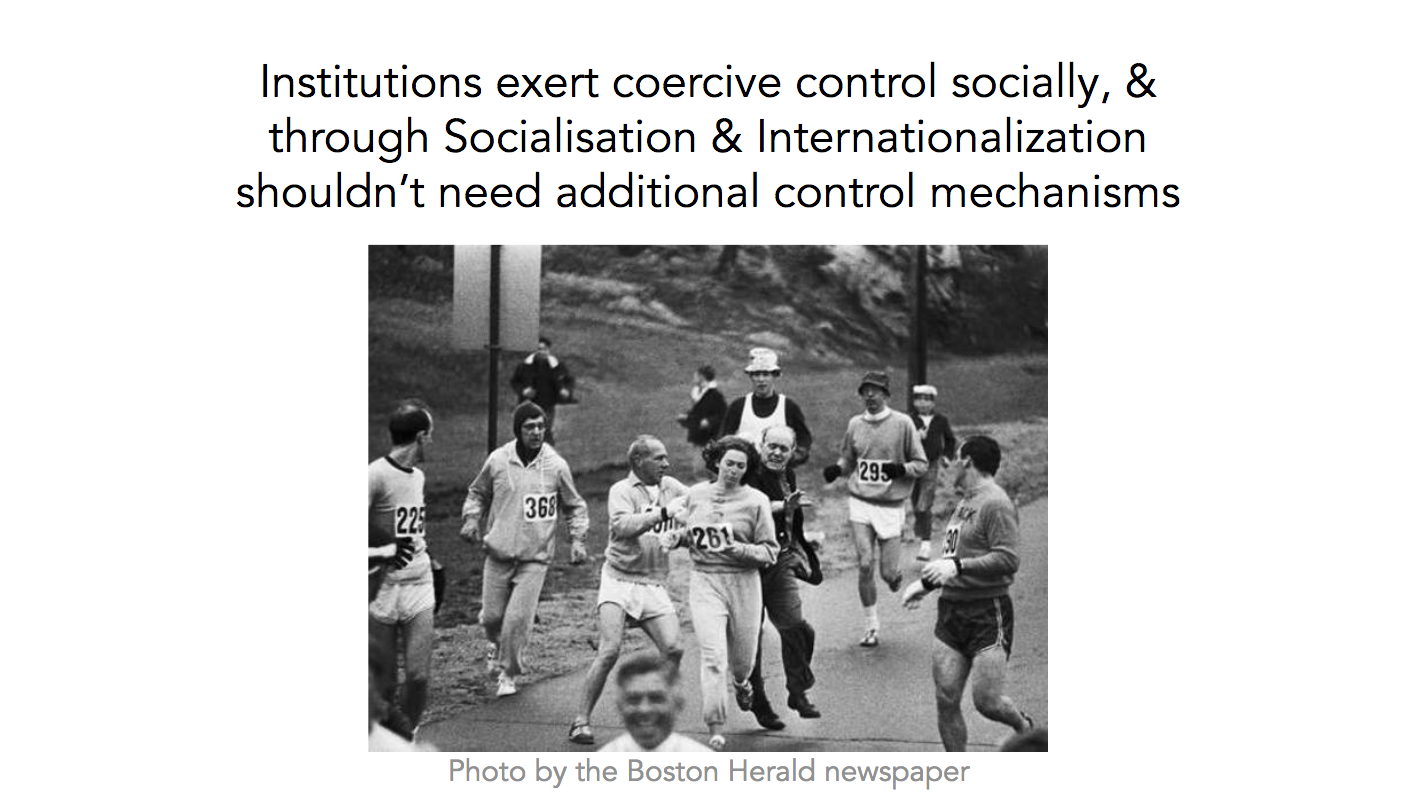

So, if successful, all these processes contribute to us thinking that there are these kinds of people that can do these kinds of things. We internalise the rules and make them our own. Let’s take this famous moment in sporting history: Kathrine Switzer is running the 1967 Boston Marathon. As Switzer recounts in her memoir: this photo is the moment when the race official Jock Semple came running up behind her yelling “Get the hell out of my race and give me those numbers!” And tried to rip of Switzer’s race numbers. It was then her boyfriend Thomas Miller gave Jock a cross-body blow to push him away from Kathrine and let her run. You see, for 70 years, this had been a male-only marathon. But when Switzer and her trainer were entering the competition, they looked through the rulebook and found no rules about gender. The marathon had been male-only for 70 years because everyone, male and female-identifying, had successfully internalised the institution of sport, of men being the only ones physically capable of running marathons. They had internalised the rules around who can do what. So the idea of putting a rule in there didn’t need to happen. When the race official saw Kathrine challenging that social order, he exerted his own social control by attempting to rip of Switzer’s race numbers. But last year, Switzer ran the Boston marathon again, 50 years after this historic first run, and with the same race numbers: 261.

All this effort, over time, contributes to the social construction of reality. And this is where it gets really interesting. Berger talks about realities and universes somewhat interchangeably and talks about how these (and other) processes construct not just one reality, but many realities.

Here are four key realities or universes. I’ll be using these terms interchangeably. Now Berger doesn’t actually mention four. He discusses the paramount reality or universe, and talks about reality maintenance and reality metamorphosis. The fourth human activity of creation is implied but I’ll be offering some further thoughts on how this one operates.

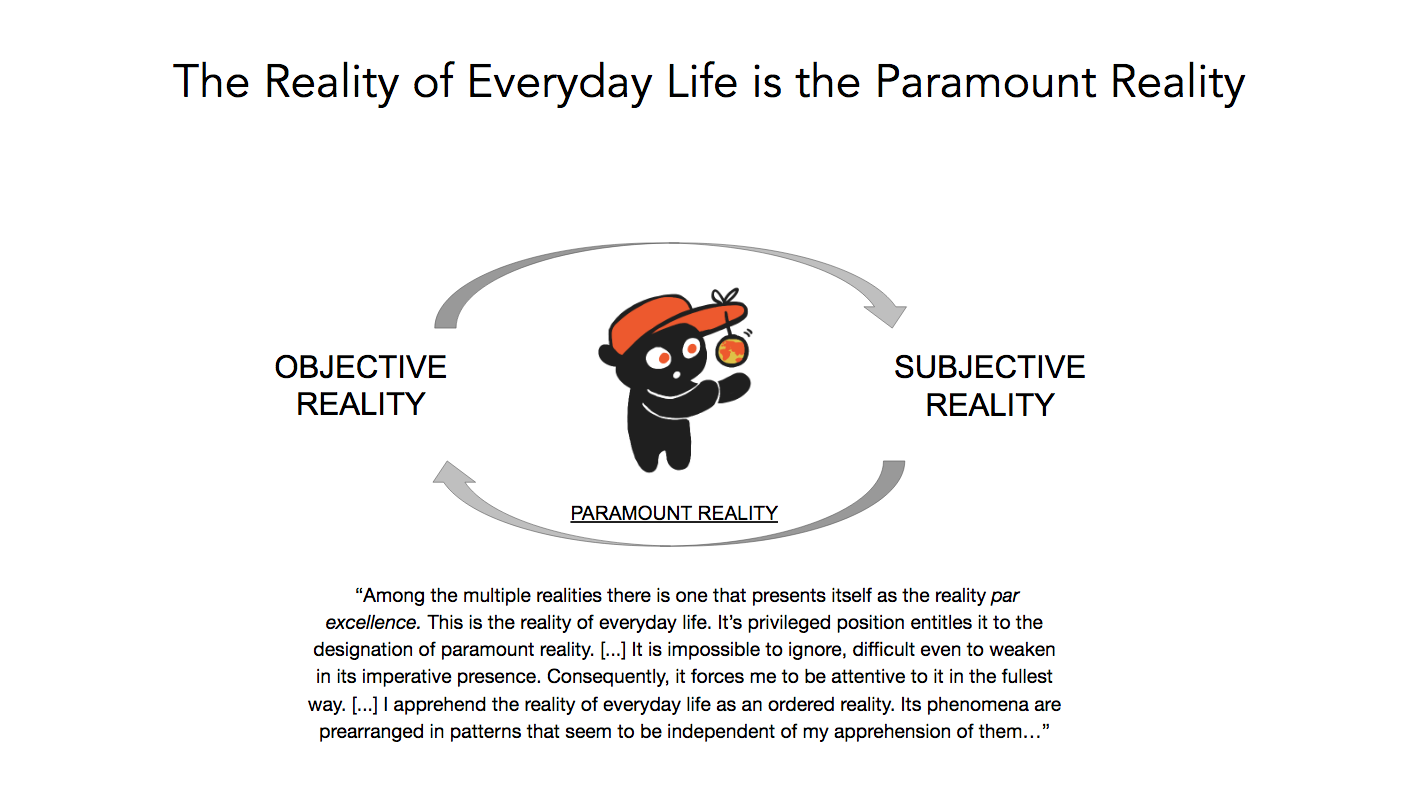

Paramount reality is the product of everything we’ve been talking about. Berger explains that “Among the multiple realities there is one that presents itself as the reality par excellence. This is the reality of everyday life. It’s privileged position entitles it to the designation of paramount reality. […] It is impossible to ignore, difficult even to weaken in its imperative presence. Consequently, it forces me to be attentive to it in the fullest way. […]”.

They continue, explaining how the reality of everyday life is taken for granted as reality. It does not require additional verification. It is simply there, as self-evident.” “Everybody knows” it is real. The paramount universe is where the majority of all our creative projects are made from. Our creative projects are an externalization of what we know. Berger calls the paramount reality a naive one, in the sense that we can operate in it unconsciously. There is the belief there is one universe, and so we create for it. This is why we have creatives claiming that their work is neutral or apolitical. They have internalised all the types, all the roles, all the rules about how paramount reality works and assume it as self-evident, as objective. These kinds of projects are produced because the paramount universe is part of the everyday of the creators, part of the every day of the studios.

But not everyone who creates works for the paramount universe agrees with all aspects of the paramount universe. I have consulted on these kinds of project, and I have many colleagues around the world who do actively challenge many parts of paramount reality — such as the typified roles of males and females, and marriage, and hierarchical views of race, ability, gender, and sexuality — they actively challenge these things and even live “unconventional” personal lives themselves, but they create works that operate quite nicely in the paramount universe. What does this mean?

Now, Berger does talk about how we can have enclaves of variance in our universe. We can integrate differences into the paramount universe easily if they don’t affect your routines. If you still get up, go to work, kiss your partner goodbye, visit family, and so on, then the differences are unproblematic. If your habits remain the same, your routines continue, then then paramount reality can remain unchallenged.

So, can creative projects that have a paramount reality stance, do good? Can’t we just have fun, why do we have to say something? The problem is, we’re always saying something. If we haven’t thought about the impact of our work, then we’re producing creative projects that take an uncritical stance, they present reality “as if it is”. When they’re done unconsciously, automatically, then we’re using the short-hand of agreed types, roles, and rules: let’s play with our ability to exert social control by being horrible to people, let’s remind them that there is a right way to be and anything else deserves consequences; let’s treat land as something to be taken and mined, to produce and make without ritual and care. It is so easy to create in this reality because it is automatic. We believe we’re just using what makes something funny and fun because it is human nature.

Comedian Cameron Esposito has commented about colleagues who have difficulty telling jokes (in the manner we would describe as paramount reality). Cameron mimics their concern “How can I tell jokes? How can I tell jokes without all these words? I need them.‘ And I’ll just say, “If they’re any particular word that you need to use to do this job, I am a better stand up comic than you.” Indeed, it is the reality we create when we don’t realise we can create our reality. Works set in the paramount universe don’t exhibit qualities of a reality-transforming work. Like a roller coaster ride, we end up where we began. All works are always saying something, and works that echo the paramount universe present a world someone else has written, despite what it says in the credits. Can you just make works for the fun of it, without trying to do something though? Yes, and I’ll talk about that soon.

For now, I want to note that many of my colleagues create works, films, reality TV shows, TV shows, books, plays, and games, they create all these for the paramount reality because of income. They know on some level they’re telling a lie, but they believe the only way to make money is to make content for the paramount reality. It is the question of whether we can make money from anything but the status quo. It is true that many of our institutions, our systems are set-up for this. But remember the inevitably illusion, paramount reality is not the only reality. There are other realities, and markets. Because these realities are also markets.

We spoke earlier about how we internalize paramount reality. If we believe it is inevitable most of the time, then our socialization is successful. But, Berger explains, there is “always the haunting presence of metamorphoses […] the competing definitions of reality”. Berger talks about other universes that increase in their sophistication from the naive mode. And I find this sophistication is in part because they involve an awareness of our role in co-creating our reality, and techniques to action this. We’re taught how to craft games, but not how to shape the world. But as creatives, we can make projects that question and seek to transform paramount reality.

The Matrix was about the choice to wake up from the illusion we’re told is real, or choosing to see that it is constructed. It is a tale we see in creative projects throughout time in many forms. People can’t engage in changing paramount reality if they don’t first realise that reality is constructed.

Rod Sterling’s The Twilight Zone sought to show the surreal nature of reality, questioning reality, and embedding within it tales of hope, along with his production processes like likewise challenged conventional structures. It was through TV, through fiction, that Sterling believed more could be said.

Another approach is to also bear witness to how paramount reality affects us, in different ways. James Baldwin’s essays, first published in The New Yorker in 1962, and then as a book in 1963. In the first essay, Baldwin’s addresses his 14-year-old nephew on the one hundredth anniversary of emancipation. [READ out pages 26-27]

“Every effort made by the child’s elders to prepare him for a fate from which they cannot protect him causes him secretly, in terror, to begin to await, without knowing that he is doing so, his mysterious and inexorable punishment. He must be ‘good’ not only in order to please is parents and not only to avoid being punished by them; behind their authority stands another, nameless and impersonal, infinitely harder to please, and bottomlessly cruel. And this filters into the child’s consciousness through his parents’ tone of voice as he is being exhorted, punished, or loved; in the sudden, uncontrollable note of fear heard in this mother’s or his father’s voice when he has strayed beyond some particular boundary. He does not know what the boundary is, and he can get not explanation of it, which is frightening enough, but the fear he hears in the voices of his elders is more frightening still. The fear that I heard in my father’s voice, for example, when he realized that I really believed I could do anything a white boy could do, and had every intention of proving it, was not at all like the fear I heard when one of us was ill or had fallen down the stairs or strayed too far from the house. It was another fear, a fear that the child, in challenging the white world’s assumptions, was putting himself in the path of destruction.”

More recently, Jordan Peele’s feature film documents the horror of race relations, and topped the box office with a black lead. Perhaps the rules about what is profitable aren’t true after all? No perhaps. There is more than one reality. Interestingly, it has been announced that Jordan is hosting the next Twilight Zone reboot.

In music, Gil Scott Heron’s 1970 spoken-word jazz track “The Revolution will not be Televised” reminds us that change is in our hands: the lyrics include “The Revolution will put you in the driver’s seat […] The Revolution will be live”. “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me ‘Round“ is an African American spiritual song, with the lyrics on keeping on walkin’, keepin’ on talking, marching into freedom land. Midnight Oil’s song “Beds are Burning” is a call to act “how can you sleep while your beds are burning?”. In the documentary just released called “1984: Midnight Oil”, old footage of Peter Garrett, the lead singer, is addressing school kids. He says “I don’t think politics means you’re old enough to vote. […] I think politics means the understanding that you can change the way society affects you.” Beyoncé’s “Formation” is a powerful collection of scenes and moves of empowerment, with the lyrics “I dream it, I work hard, I grind ’til I own it“. It is a capitalist dream, but it is form of power. Childish Gambino’s “This is America” takes aim straight at racism throughout time and at present in America. And Amanda Palmer’s recent music video “Mr Weinstein will see you now” includes the end sentiment of taking over writing the story in the face of others trying to deny the truth of your own reality. “I’m writing this”.

We see it in the comedy of Bill Hicks and now Hannah Gadsby. Gadsby makes it clear there is a personal cost to producing content for a paramount universe. Gadsby had to be willing to give it all away to take on her reality. What Gadsby discovered was that there is a market for different realities. It does require using different narrative and interaction structures though. Most of our rules of creative practice are rules that work for the status quo, not for those wanting to transform. For all the talk in games about having agency, most games do not encourage you to have agency in your own world. But let’s look at ones that do.

An early example is Chris Crawford’s “Balance of Power” (which he made using his severance for a company he was just laid off from). It is set in the Cold War, and is a criticism of the structures that support war, power, and the use of nuclear power. Crawford said Bob Dylan’s song “Blowin‘ in the wind” was an influence on making this game promoting peace.

Gonzalo Frasca’s game September 12th puts you in the position of killing terrorists, only to find killing does not actually reduce the number of terrorists, it increases them. The New York Times described September 12th as “An Op-Ed composed not of words but of actions”.

MolleIndustria’s games are all designed for culture jamming. A popular example is “Unmanned”, a critique of drone warfare and masculinity.

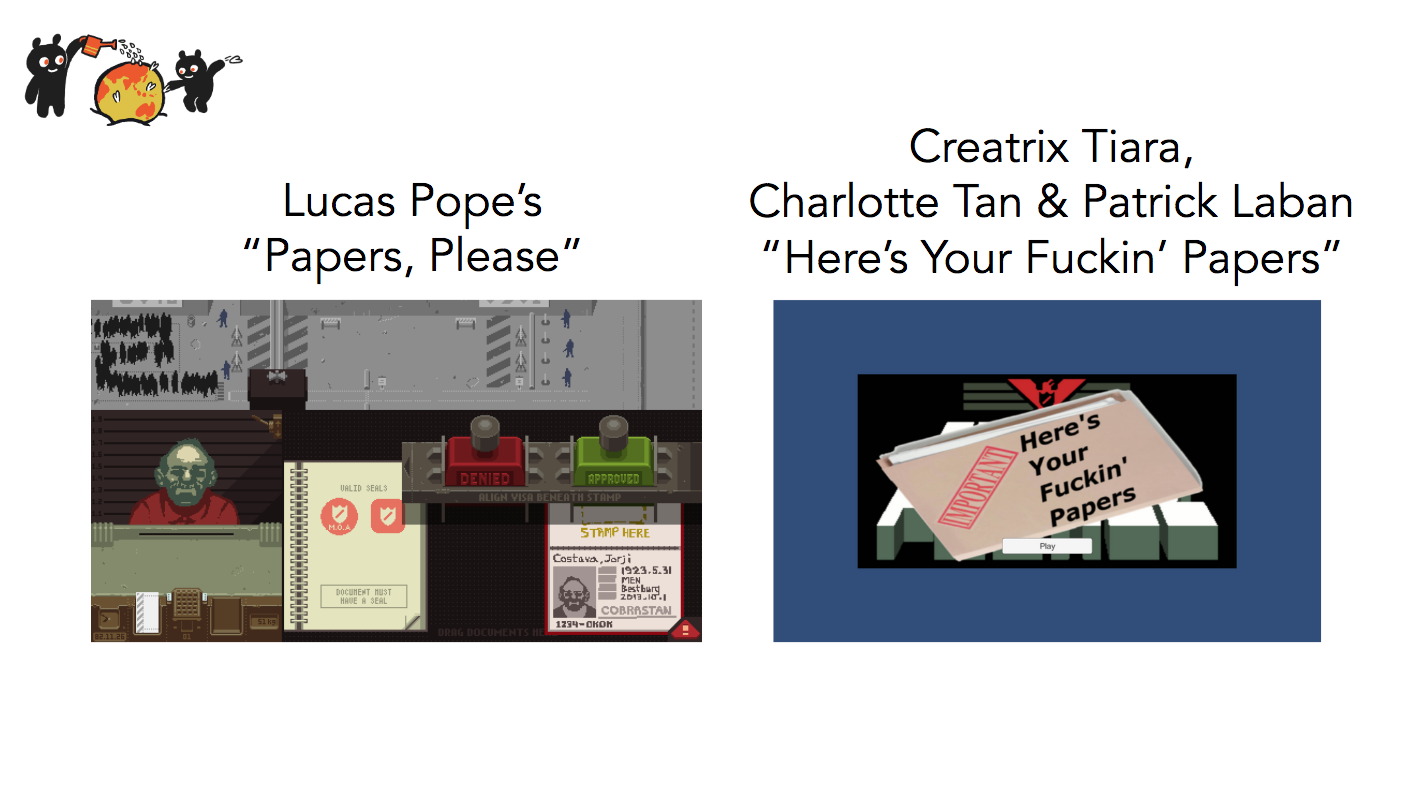

The 2013 “Papers, please“ game gives us moral decisions as an immigration officer around supporting our own family and being humane to others – it is in some ways documenting the tensions of working in paramount reality for the sake of an income. It was a critical and commercial success, and within 3 years of release (back in 2016) it had sold over 1.8 million units and won numerous awards. A short film has just been released too.

“Here’s Your Fuckin’ Papers” switches the perspective to the person trying to cross the border, and highlights the difficulties one faces with changing bureaucracies. Proceeds of the game were going to organisations assisting in immigration and passports. That game was made at GaymerX’s GXDev…

Indeed jams often operate to facilitate games for reality transformation. The Resist Jam that has tons of resistance games made by creatives from around the world. Including one that sets Papers, Please in current Canada. These are all released on sites like itch.io, which don’t gate-keep, don’t use social control.

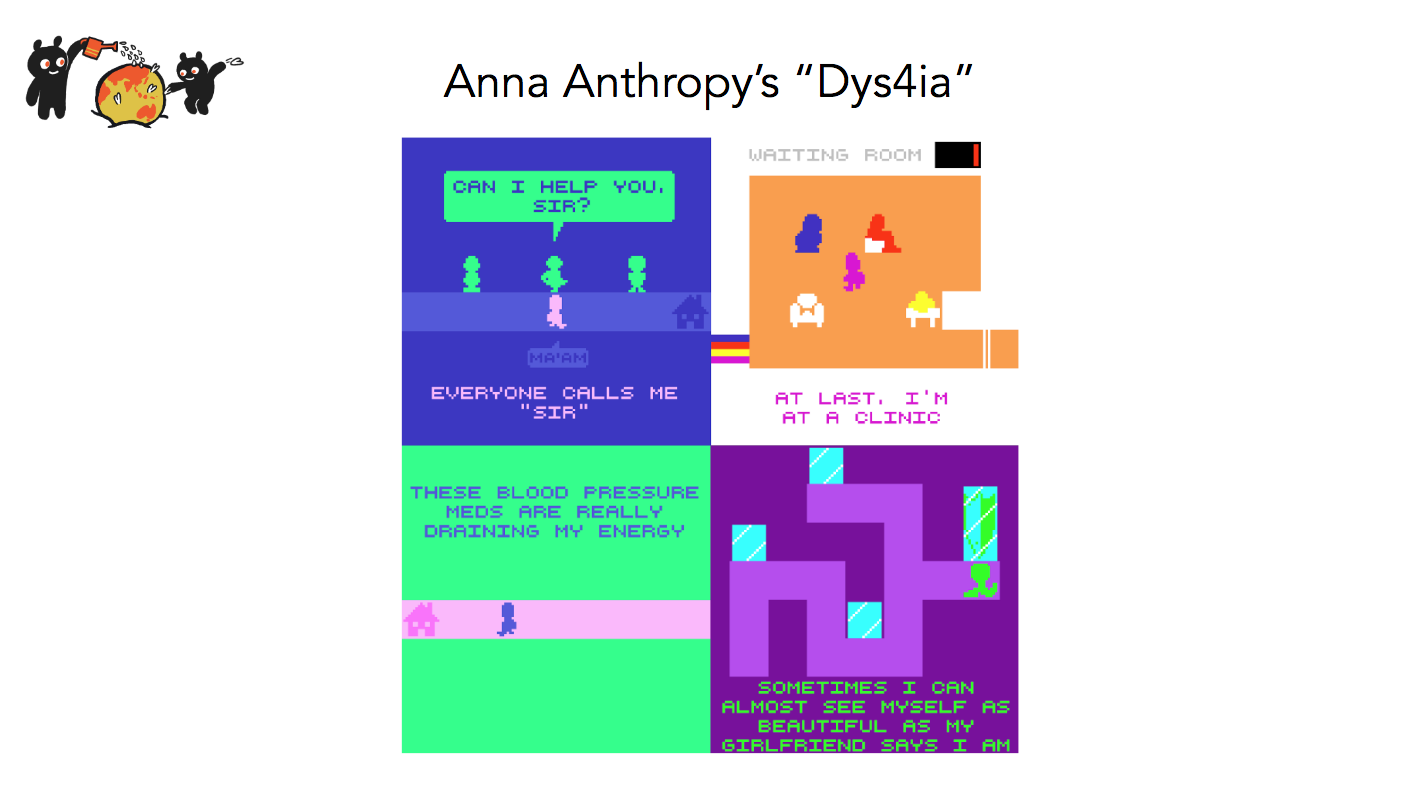

Anna Anthropy’s Dys4ia is an autobiographical game that actually opened up the personal game area, and is described by Nick Fortugno (the designer of Diner Dash) as “the most powerful translation of the experience of gender reassignment in any medium — ever.” This game was available for free for a while, then paid, and now it free again. Anna has…

Night in the Woods is an adventure game, that through the storyline of allegorical characters who experience mental health issues (from the developers’ personal experiences). It is available on desktop, tablet, mobile, playstation, xbox, and switch. It has won numerous awards and has been listed as one of the top games in 2017. It has critical and commercial success. In Berger’s book, therapy is listed as one of the social control mechanisms used to get people to return to reality. We will all be familiar with historical cases of terrible uses of therapy, and some current. But thankfully there are therapists that don’t try to make you something different, and the developers comment on how important it is to find the right therapist.

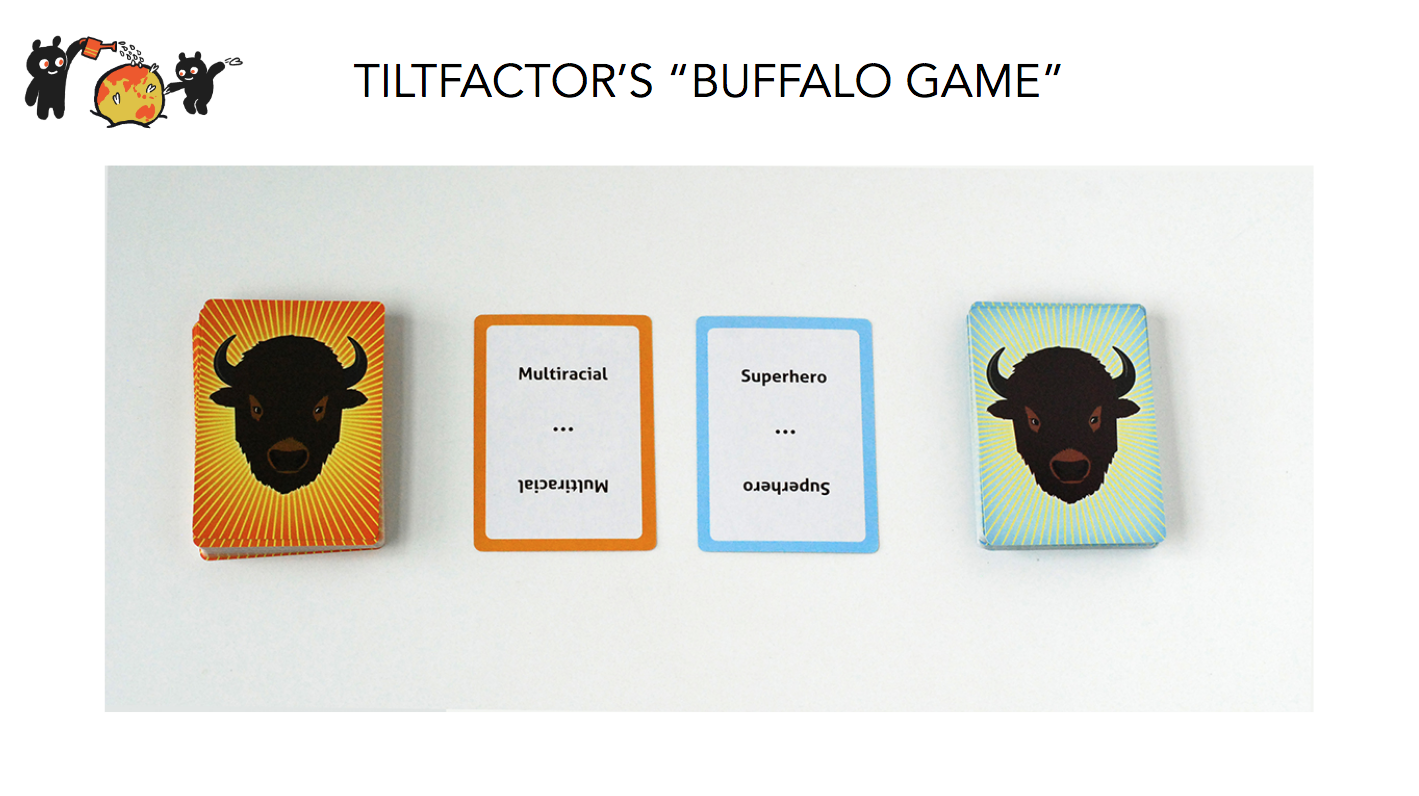

Tiltfactor’s Buffalo is a party game for adults and families (2–8 players ages 14 and up). Your aim is to collect as many cards as possible by quickly name dropping a response to the blue and orange prompt cards. What you won’t see in any of the game descriptions on the box or at the online stores, is what the game is actually designed to do. It is a game that subtly reveals our unconscious biases. It was developed with funding by the National Science Foundation for this purpose. Intentionally, the game is using what the designers call “stealth” – it isn’t telling people what it is about and simply allowing players to come to realisations themselves while they play. It is in this sense a emergent dialectical rather than scripted dialectical.

I want to highlight here the market for these kinds of projects, and many of these works have ongoing resonance for years. They are stand-out hits both critically and commercially. There are some works that are not sold, they are released free. The artists garner income from other sources. Wild successes are due to them being a well-written and designed experience, that also has a message or transforming affect. There is great skill involved with this approach. Some are known for their message and some operate with stealth. One point I want to highlight here too, is the player or audience desire for these types of experiences. I see some serious games aimed at people who aren’t interested in changing. A racist person isn’t interested in picking up a game about racial discrimination. That is why some projects are about being a great entertainment or art piece in themselves too and operate with stealth. But an under-utilised market is people interested in self-transformation. Rather than aiming your creative works at people you want to change, instead, you’re creating works for people who consciously want to change something about themselves. Some of us don‘t need a wizard to come knocking at our door before we want to step up and be a better person. That is the market I’m aiming for, and one that relates to our last reality category. But before we go there, we need to briefly look at the pushback to reality transformation.

Universe Maintenance occurs when there are problems with the paramount universe. It occurs when socialization from one generation to the next hasn’t been successful. Why can’t two women marry mum? It also happens when there are conflicting universes, and each of these universes have ways to maintain their own realities. There becomes enough of an alternative. There are different methods used to get us back to “paramount reality” which is considered the best reality.

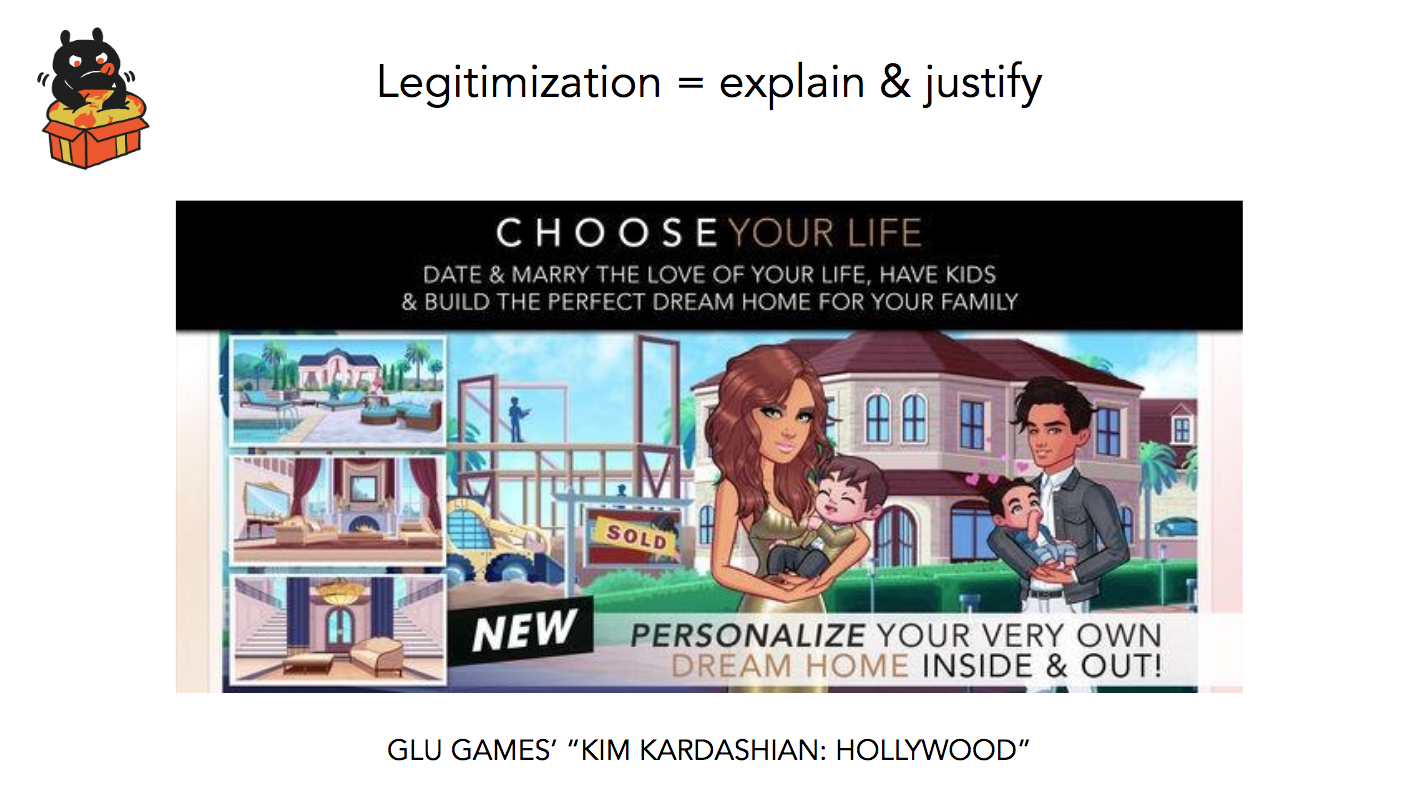

The passing on through generations doesn’t always work because each new generation doesn’t have access to memories of the activities first-hand. The types and actions and rules become “realities divorced from their original relevance”. Everything becomes hearsay. Legitimization is about explaining and justifying why things happen. They need to be consistent and comprehensive if they are to carry any conviction for the next generation. The institution of celebrity, of fame, has successfully passed down through more than one generation, and has transformed to keep being relevant. You get famous, you get a husband or wife, you have kids, you keep being in the public eye and you can afford assistants and nannies. You can have a family, and be famous, and run your own company. Fame gives you independence. All humans desire to have a family and be known and live the good life, and some of us are better at it than others. Only the most selfish and cut-throat win. It’s just the way it is.

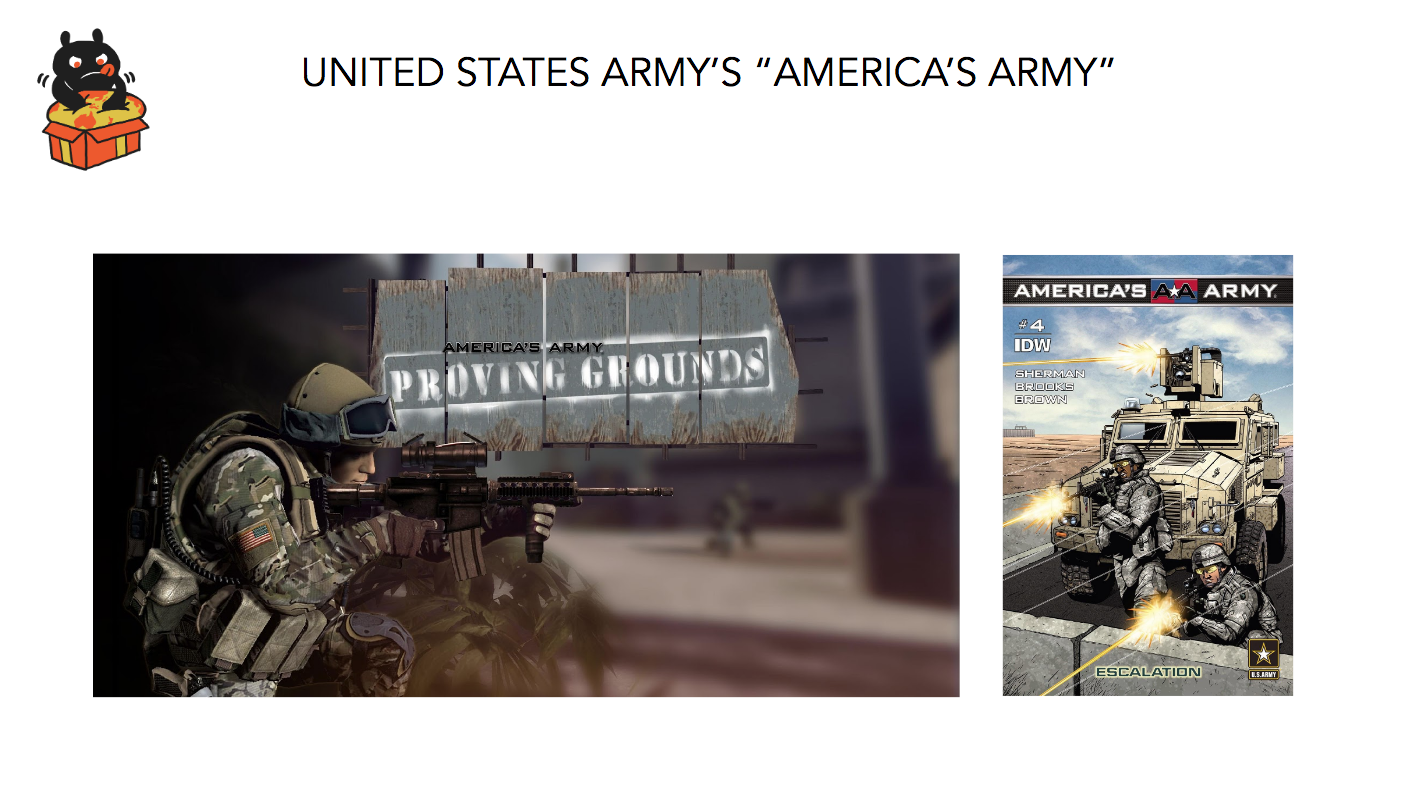

Every generation has justifications for war throughout all mass artforms — film, TV, novels, games. It has to keep being repeated over and over again why we do this.

Our reality TV shows about Border Security (I see you have this on Swedish TV), Police, SWAT, etc – all of these aim to legitimise paramount reality, the rules, the types, and the social consequences of deviating.

An important aspect of the language universe maintenance is about returning to a reality, a reality that is framed as being paramount, as logical, as better. It is not about moving forward or transforming what we know, it is about returning to what was known before. The claim is that the discomfort anyone feels is not because of paramount reality, it is because we have deviated from paramount reality.

There are games that seek to exert overt social control through showing the consequences of deviating from paramount reality. These games involve mass murder, rape, and other crimes against humanity. I have chosen not to show them here. Because their existence, their words, have power.

Unfortunately, there is the belief that hearing out people’s thoughts has no power. I think people believe that power rests with law makers? But as Berger has shown, it is in everyday conversations that reality transformation occurs. So when journalists claim to be objective in their reporting, they’re forgetting that words are not benign, they’re incantations.

We all have a role in reality construction, whether we are aware of it or not. I have actually worked on an App that was for Universe Maintenance. It is a Pick Up Artist comedy series. It was funded by Screen Australia, and received an Australian Directors’ Guild award. I mention this project because, 8 years ago, I consulted on it. At the time, I thought my colleagues were naive about their understanding of women, but it wasn’t until I saw more of the content and posts from them that I realised the entrenched worldview they were coming from. Some of you may be working on such projects, and I hope you are hearing that there are alternatives. The last one I will mention here is Universe Creation.

So Universe Creation. The difference here is that rather than aiming your creations towards maintaining or changing existing realities, your focus shifts to co-creating completely new social realities. In order to do this, your focus involves looking deeply at yourself. You look into the melting pot and face yourself. Let me explain this further.

Years ago, I was developing an interactive comedy about the meaning of death. It was after my mum’s sudden passing from a brain aneurysm, and I was channeling my grief into a creative project. I was working on the dialogue and having such a hard time getting it right. I wanted it to have the same wit and insight as a lot of Sorkin’s dialogue from West Wing has. Now, dialogue is hard anyway. But the problem was being exacerbated by something else. I wanted my characters to give witty come-backs that get the crux of the matter. And I couldn’t, I couldn’t because I hadn’t been living it. I was not practiced in speaking my mind, let alone speaking my mind with eloquence. Some may be thinking “that is what writer’s do, they make it up”. Sure, there are things we make up – settings, characters, objects, plots. But everything comes from somewhere. If you’re writing characters you don’t know about, then you’re either drawing on cliche or yourself. This is why we have so many ”strong women” characters that don’t quite ring true. They’re not being written from a point of personal experience with strength. I wanted to write dialogue that represents how I experience being witty and true. Funnily enough, it was at that point when I decided that I was going to be more forthright in my everyday interactions. So I could make better projects. If you’re going to create something new, then you need to be new. Your creative project can only stretch the imagination as far as you have personally stretched your inner world.

I’m going to give a brand example here. Hesta is a superannuation company in Australia. Their aim is to “make real differences to the lives of our members and also women in Australia”. Women have less superannuation than men but they live longer. The things I wish to highlight is that this value, this goal of the company is only possible because of the work the company has been doing internally with their own culture. There are many brands out there that ring the woke bell, but don’t live it in the everyday. The things you create in the world are a reflection of how you live in the world. Your everyday.

The Wachowski’s created a world where polyamorous lifestyles, and roles and types, and our sense of time and space are all part of a fully realised new reality. None of this could have been conceived or created without the Wachowski’s doing the internal work. These projects are externalisations of an internal reality.

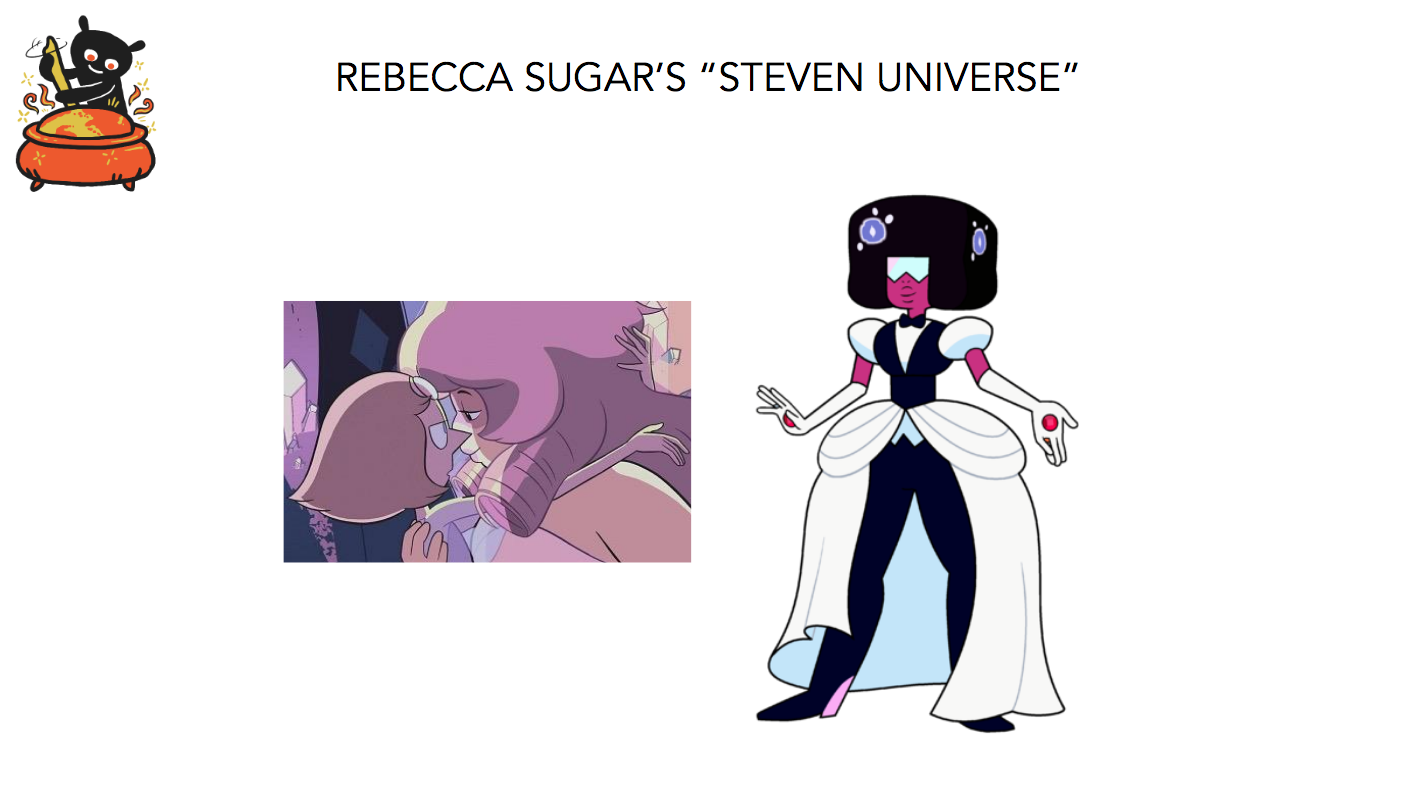

The same with Rebecca Sugar’s Steven Universe is producing characters and plots that make new types and roles normal.

John Lennon’s Imagine – asks us to image the world we want, and to feel it. More recently, this music video was just released, and features the lyrics “I’m not a boy, I’m not a girl, I’m fractal”. It depicts an environment with lots of people enjoying their own fractal identity, a celebration of just being.

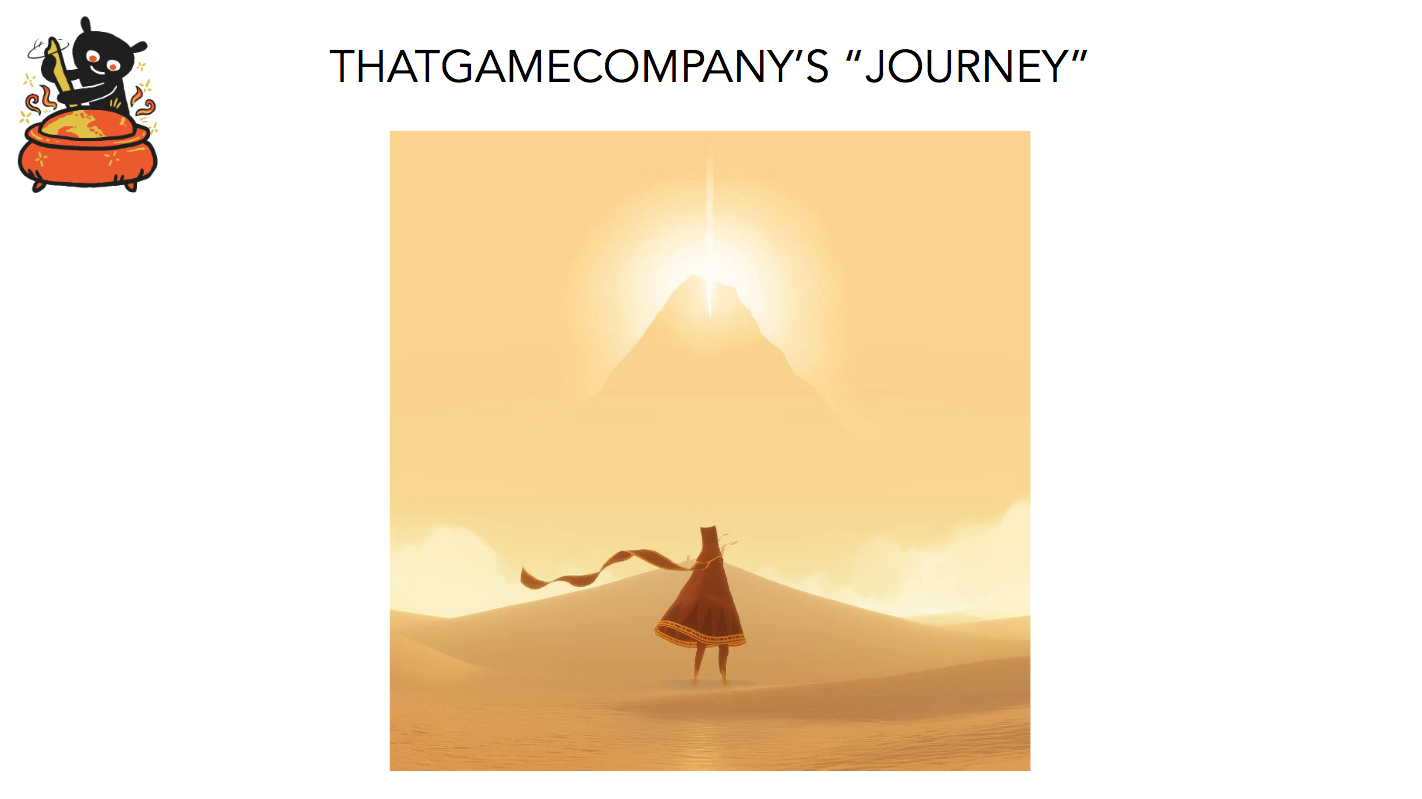

Journey is a world where the journey of your life is in doing the internal work and then turning to reach back and help others on that journey. It was a commercial and critical success.

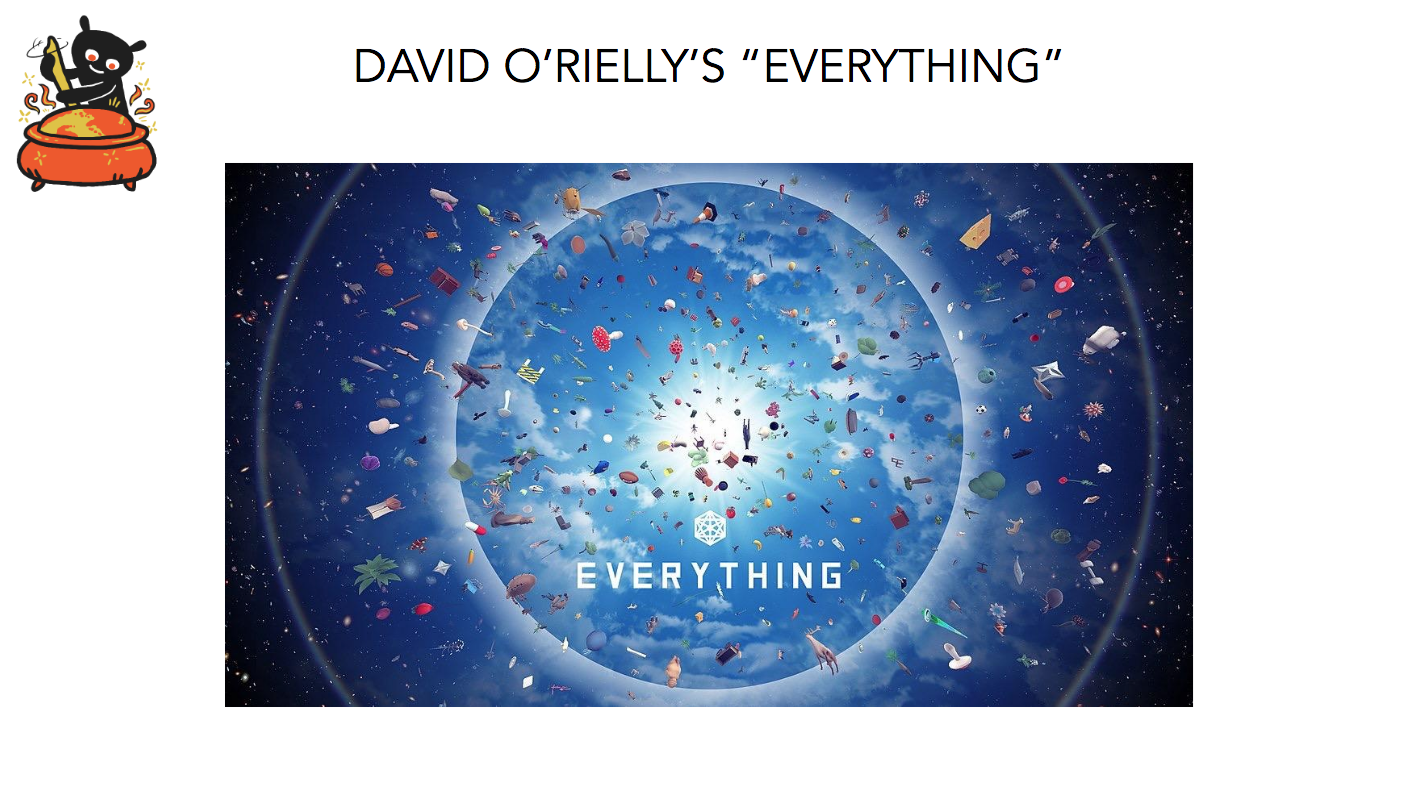

David O’Rielly’s “Everything”. You can begin as a bear, and can move your consciousness, your POV to that of a horse, a flower, to a star. It is narrated with edited recordings of philosopher Alan Watts. Polygon described it as “the most true-to-my-life game I’ve ever played”, and The Washington Post described it as a “rare game that may push you to want to lead a better life”.

Mister Rogers’ Neighbourhood had the same affect on people. The TV series had people lining up around streets to meet Fred. The doco on the series premiered at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival. It received acclaim from critics and audiences and has (at the time of writing this) grossed over $22 million, making it the highest-grossing biographical documentary of all time.

There is also another biopic coming out almost to year from this day. The film is based on the true story of the friendship between Fred Rogers and journalist Tom Junod. Tom is a jaded Esquire magazine writer who is reluctantly assigned to profile Rogers. But his “whole world changes when coming in contact with Fred Rogers”, he is so moved by Rogers’ kindness and empathy that he overcomes his skepticism and has a renewed look on life.

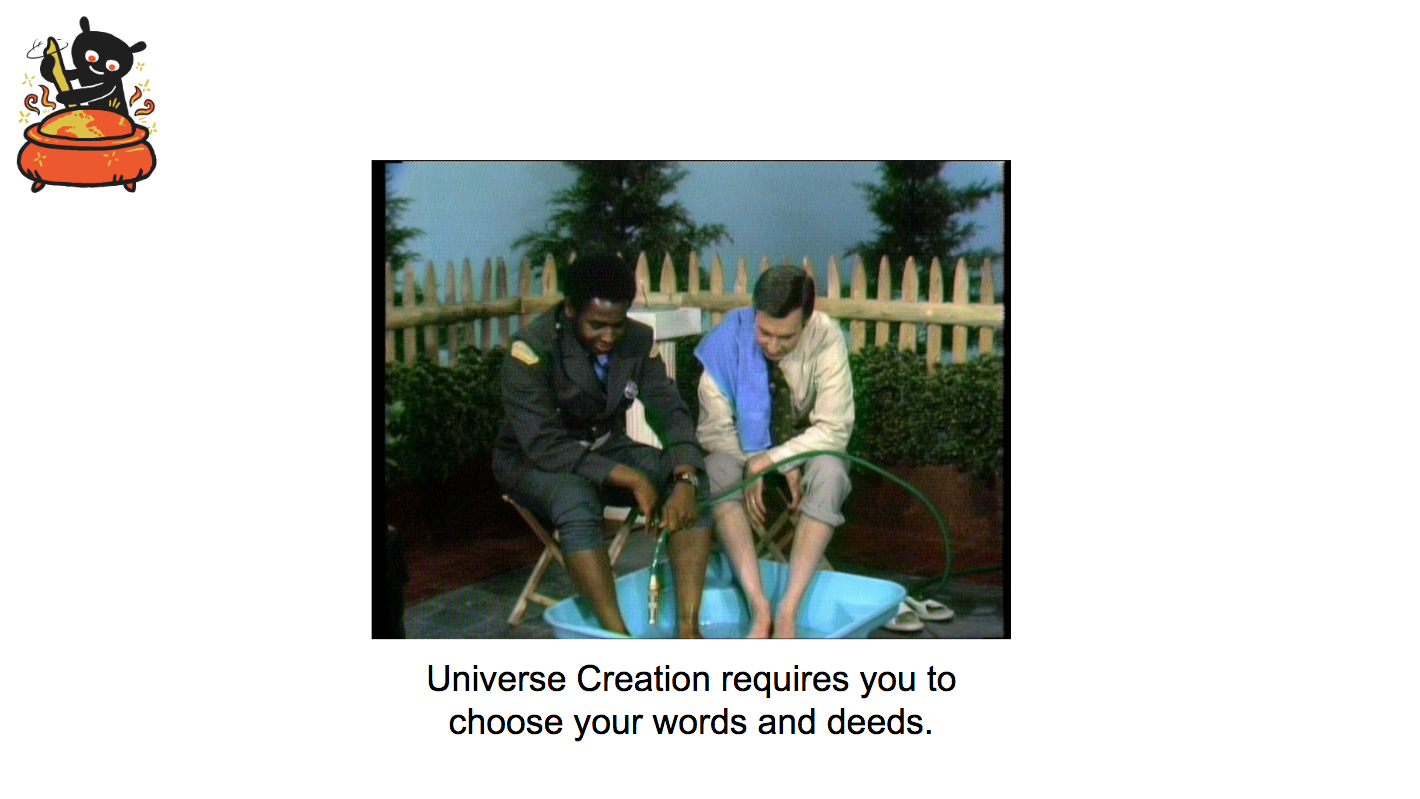

An important moment from the original series was when Mister Rogers invited Officer Clemmons to join him in cooling in the pool. This is in the context of segregation happening at the time of this episode, where African Americans were not allowed to swim in the same pool as white Americans. Universe Creation can be these simple moments. This is where you can just create something that is fun or just is, but it is the result of internal work. You can just make, you can just be, when you choose to create the way you want to be.

The studio Tru Luv, headed by ex-lead AI programmer for 3 Assassin’s Creed games and Child of Light, Brie Code, is described by Slate as a “studio devoted to a radically different framework built on care and connectivity”. It was an experiment by the creators, Brie & Eve Thomas, and Petra, that reached 500,000 downloads in 6 weeks. In this experience, you spend time in bed, tending to your plants, reading tarot. It is a new everyday. An everyday that has been externalised from the everyday of the developers. Brie created this from her inner work.

These are the kinds of realities that are out there, that we’re making. What if we had these as Netflix categories or PlayStation categories? You could choose your reality. How cool would that be?

So, we come back to our questions…

1) Because they predominately make “paramount” and “maintenance” reality projects.

2) See above.

3) No. There are many markets.

4) In transmedia, we often talk about the essence of the property. The reality stance of a property is another element I take into consideration. It doesn’t have the be the same. You can have projects that move from paramount to metamorphosis. But when they move from metamorphosis to paramount there will be a bigger clunk, at least in myself.

5) Yes we can, and do.

6) Yes they can.

7) Yes we can.

=====

[

[

[

[