Main Page > TIERING: LEVELS > Tiering: Types > Resources: Sources > Resources: Types > Research: Fictional > Summary > Bibliography

In 2001, the first two 'alternate reality games' (ARGs), commissioned by two different gaming studios, emerged [1]. Microsoft Game Studio commissioned The Beast to make Steven Spielberg's forthcoming film A.I. Artificial Intelligence seem a property that would appeal to gamers. The film was meant to be followed by Xbox games, and so the ARG was commissioned to "develop A.I. as an I.P. [intellectual property], as a world, as a context for building firstperson shooters, race games, gladiator games, chase games” (Sean Stewart in McGonigal, 2006, pp.267). McGonigal (2006, pp.268) continues:According to Stewart, the central creative problem Microsoft Games Studio (MGS) faced in developing the A.I. license was the film’s apocalyptic ending, which did not intuitively suggest any possibility for future play.That same year, Electronic Arts launched Majestic. ARG designer Dave Szulborski (2005, pp.113) notes that the design goals Jordan Weisman put forward for The Beast were very similiar to those Neil Young put forward for Majestic. Designer Greg Gibson (2006) explains in retrospect the goal:

Our goal was, simply, this: create an online, story-driven game to satisfy the most casual of gamers--people who could only play in short bursts every now and then. At the same time, try to keep the hardcore gamers satisfied. After considering different game genre options and combinations--before I was hired, I think Majestic was originally going to be some kind of first-person shooter hybrid--EA and Neil Young (the head of the project) decided that an ARG was the right format for achieving that goal.While The Beast attempted to provide a new artform to access the storyworld of A.I., Majestic also attempted to provide different levels of gameplay for different players. It is no coincidence that ARGs were created with these goals in mind and that they continue to provide for different audiences. In the journal essay I discuss some of the characteristics of ARGs that facilitate this goal, but here I'll delve into how ARGs since The Beast and Majestic target different players through 'tiering'.

|

Figure 1. Picture of Metallica lullaby album from Rockabye Baby! website (2008)

Other examples are found in television programmes that combine a range of genres with the aim of appealing to different audience interests. Or consider children’s story books, rides and movies that address both parent and child. For instance, 3D animated films with jokes and allusions for adults as well as children. I have included my amateur attempt at a 'visualisation' of such practices, which I hope will illuminate my point, whilst also obviously bringing you pleasure. :) [Refresh the page if for some reason the image isn't showing.]

|

Figure 2. Visualisation of Parents and Children being addressed by different jokes in a film

In all of these examples there is content within a single medium that targets a particular audience segment, but there needs to be a distinction between works that offer completely different content to be experienced entirely by different audiences. At times 3D animated films may qualify as 'tiering' because there are adult-oriented moments that are not understood by the children, but what is important to note is that 'tiering' involves a choice. If everyone is forced to experience the same content then it isn't tiering. Tiering, therefore, describes (among other things) a choice of entry into a work, or world. Alternate reality games (ARGs) are an excellent example of this notion because some ARGs are created to offer a different way of experiencing a known entertainment property (like a film or game), ARG designers tier their content for players but also because the gameplay resources that players produce creates another tier for large-scale ARG audiences. To elaborate on tiering in ARGs, I've proposed some categories to help explain how it occurs:| 1 Tier Levels: | World, Work |

| 2 Tier Source: | Initial Producer (Primary Producer), Experiencer (Player/Audience), Commentator (Media, Analysts, etc.) |

| 4 Tier Types: | Artform Tiering, Gameplay Style, Player Expertise, Geographic Tiering, Player Engagement... |

Tiers at the world level address different audiences with different works. In this context, a ‘world’ denotes the sum of productions that are set within the same fictional universe. In many ways it is akin to a brand, storyworld, gameworld or ‘verse in fan-culture parlance ('verse is short for 'universe'). In the context of ARGs, world tiering is evidenced in the so-called transmedia extensions of existing properties. These ARGs provided audiences with a point-of-entry to the fictional world through the artform they preferred to experience it through (which means it is an 'artform tiering' type). Indeed media theorist Henry Jenkins (2006, pp.96) explains the economic-logic of such an approach:

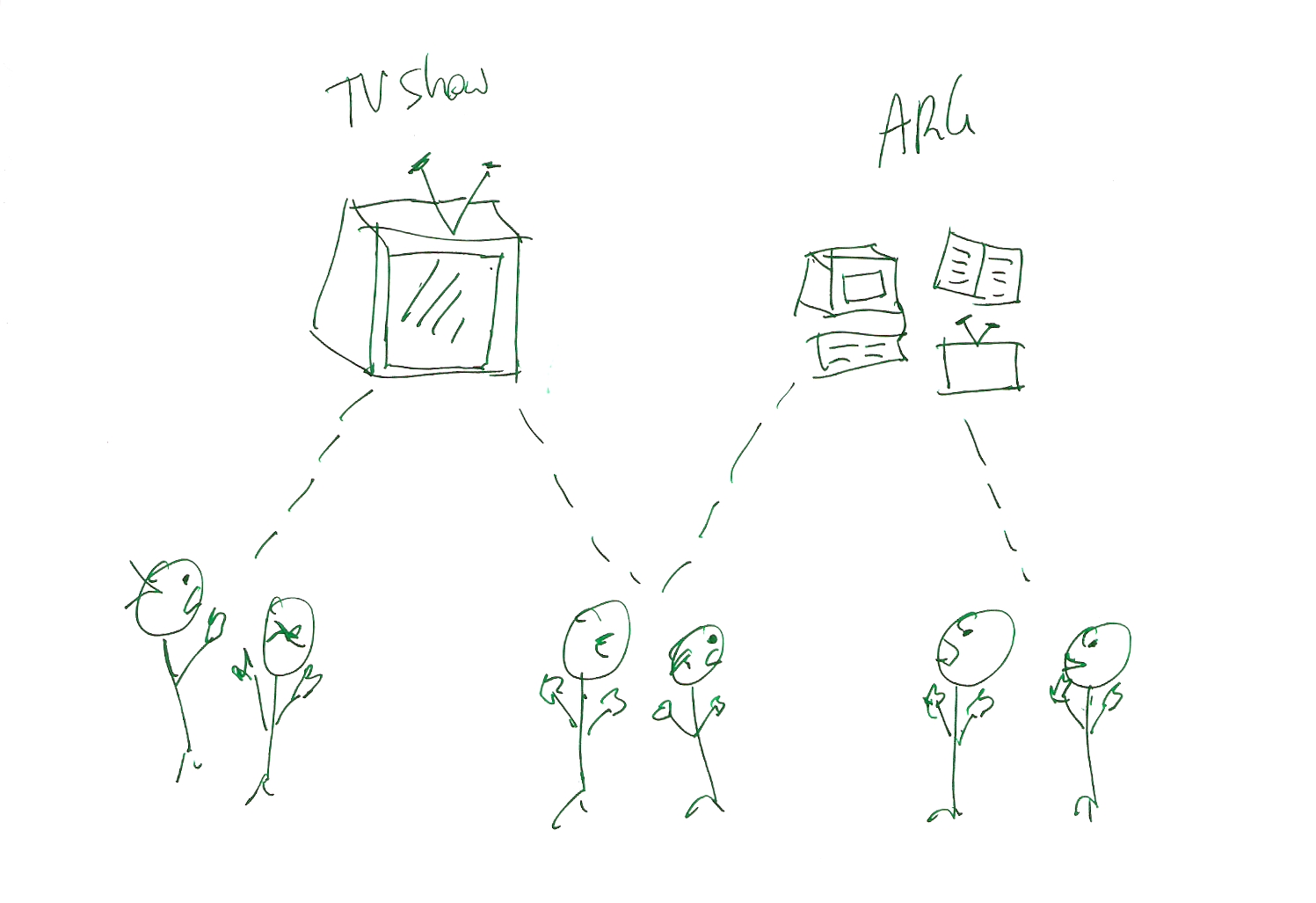

Different media attract different market niches. Films and television probably have the most diverse audiences, comics and games the narrowest. A good transmedia franchise works to attract multiple constituencies by pitching the content somewhat differently in the different media. If there is, however, enough to sustain those different constituencies—and if each work offers fresh experiences—then you can count on a crossover market that will expand the potential gross.As you will see in figure 3, some audiences may experience one artform or medium only while others experience both.

|

Figure 3. Visualisation of ARG World Tiering

Examples of properties and products that have been 'extended' to include an ARG are outlined in table 1. Some ARGs were experienced sequentially with an entertainment property (before or after it), some simultaneously, and some overlapped with both modes. But please note, these are not all the ARGs that are linked with other properties or products, not all ARGs extend a property (most are independent) and just what qualifies as an ARG is debatable (see footnote [2] at the bottom of this page).| TRAVERSAL

TYPE |

ENTERTAINMENT

PROPERTY OR PRODUCTS |

PROPERTY

TYPE |

ARG |

| SEQ =

ARG BEFORE |

A.I.: Artificial Intelligence (Steven Spielberg, Warner Bros., 2001)

Halo 2 (Bungie Studios for Microsoft Game Studio, 2004) The Host (Bong Joon-Ho, Magnolia Pictures, 2006) 4400 (USA Network, 2007) Head Trauma (Lance Weiler, independent, 2007) The Dark Knight (Christopher Nolan, Warner Bros., 2008) Jericho (CBS, 2008) |

Film

Videogame Film Television Film Film Television |

The Beast (Microsoft Game Studio, 2001)

I Love Bees (42 Entertainment, 2004) Monster Hunt Club (ARG Studios, 2007) [Before USA release] Battle Over Promicin (CampfireNYC, 2007) [Before season 4] Hope is Missing (Lance Weiler, 2007) [Before VOD release] The Dark Knight (42 Entertainment, 2007-8) Tom Tooman/Jericho ARG (CBS, 2007-8) [Before Season 2] |

| SIMULTANEOUS |

Push, Nevada Game (ABC, 2002)

Audi A3 USA (2005) ReGenesis Season 1 (Shaftsbury Films, 2005) ReGenesis Season 2 (Shaftsbury Films, 2006) Year Zero (Nine Inch Nails, 2007) |

Television

Luxury car Television Television Music |

Push, Nevada (LivePlanet, 2002)

Art of the Heist (Campfire, GMD Studios, McKinney-Silver, 2005) ReGenesis Extended Reality Game I (Xenophile Media, 2004) ReGenesis Extended Reality Game II (Xenophile Media, 2006) Year Zero (Trent Reznor & 42 Entertainment, 2007) |

| SEQ & SIMM |

Heroes (NBC, 2007/...)

Lost Season 2 & 3 (ABC, 2006/...) Fallen (ABC Family TV, 2006) |

Television

Television Television |

Heroes Evolutions (was Heroes 360) (NBC, 2007)

The Lost Experience (ABC, Channel 4, Yahoo!7, 2006) The Ocular Effect (Matt Wolf & Xenophile Media, 2006) |

| TRAVERSAL TYPE | ENTERTAINMENT PROPERTY | PROPERTY TYPE | ARG |

| SEQUENTIAL | Minority Report (Steven Spielberg, 2002)

The Matrix (Wachowski Bros., 2003) THX1138 (George Lucas, 1971) Alias (JJ Abrams, ABC, 2001-2006) |

Feature Film

Feature Film Feature Film Television |

Exocog (Jim Miller/Miramontes Computing, 2002)

Metacortechs (various, 2003) [Before Matrix Revolutions] SEN5241 (Virtuquest, 2004) [Before DVD release] Omnifam (various, 2005) |

That's been a really interesting desire with a lot of upcoming productions [...] the way that they don't just have a single point of entry, they have multiple points of entry and all of them are meant to engage the certain type of user that comes through that medium. So, what I've been working on just a little bit is a way that people can interact with the characters of a television show to the point where they become interested in the show and that point of entry is actually through the website to the series. Yeah, I mean there are many ways. It's sort of a new method of looking at finding an audience and engaging them.One way to manage points-of-entry is to make each work self-contained and therefore requiring no knowledge of the other. ABC’s The Lost Experience (2006), for instance, involved an ARG expansion of the property that only a portion of the television fans would have participated in (and new audiences as well). Senior vice president of marketing at ABC Entertainment Mike Benson (Gaudiosi, 2006), explained that the game was 'designed to allow individuals the clues needed to put the story together on their own, whether they’re new to the show or devoted Losties'. It is important to sustain therefore, as TV theorist Jason Mittel (2006) warned, ‘two storytelling modes’:

Producers must ensure that whatever is revealed in the ARG is not needed to comprehend the TV series, as the audience of millions for the latter will certainly dwarf the number of players who will stick through “Experience” until its conclusion this fall. Additionally, “Experience” is running simultaneously across the globe, but Lost’s schedule outside the US is significantly lagged--for instance, the UK is just now getting episode 7 in the already completed season 2--meaning that any plot revelations in the ARG must be sure not to spoil mysteries within the television series. Thus “Experience” must offer only supplementary inessential narrative information to Lost, allowing the television series to retain centrality within the storyworld.This hierachical approach (of providing nonessential or secondary information) in the ARG format is what they did, as Co-Creator and Co-Executive Producer Carlton Cuse (Lachonis, 2007) explained:

The details of the Hanso Foundation’s demise [the ARG]…it’s tangential to the show but it’s not unrelated to the show. We sort of felt like the Internet Experience was a way for us to get out mythologies that we would never get to [...] in the show. I mean, because this is mythology that doesn’t have an effect on the character’s lives or existence on the island. We created it for purposes of understanding the world of the show but it was something that was always going to be sort of below the water, sort of the iceberg metaphor, and the Internet Experience sort of gave us a chance to reveal it.Co-Creator and Co-Executive Producer Damon Lindelof (Lachonis, 2007) also confirmed that although the information was 'tangential', it was nevertheless 'canon'. This tangential approach is a fairly common approach at the World Tiering level, but the factors influencing the uptake of this approach vary and will not be interrogated here. While the 'tangential' approach is intended to preserve the television medium as the primary (indeed only) channel of critical narrative information, the lack of substance in The Lost Experience did cause issues for the players. In their discussion of how The Lost Experience addressed casual players only and with little information, Andrea Phillips and Adam Martin (2006) wrote in the Alternate Reality Games Special Interest Group Whitepaper:

Games such as The LOST Experience show some of the potentially fatal dangers inherent in this: provided as a link between successive seasons of the TV show LOST, the ARG did not in any way significantly advance the plot and provided only very limited interaction with the few core characters that were even present. The game ended up leaving many people feeling let down, both ARG players and LOST fans alike, probably because it broke a cardinal rule of ARGs: artificially restricting the game within a set of media and a small set of plot directions. The ideal approach from an ARG perspective would have been to allow the story to flow freely through the game, although this would have forced TV viewers to at least read summaries of the game if not actively participate, merely in order to carry on watching the next season.CampfireNYC tackled the problem in a different way. For Battle Over Promicin, CampfireNYC (2007) had to 'excite the existing 4400 fanbase while also creating interest among non-fans and lapsed viewers'. 'The challenge,' they continued, 'was finding a way to create a compelling marketing story that would engage an audience already schooled in The 4400 mythology without chasing away potential Season 4 fans who might see the first three seasons as an imposing barrier to Season 4 viewership'. Their solution was not to explore a tangent, but to fill in gaps not addressed in the TV narrative:

At the end of Season 3, Promicin was being distributed to the general public. In Season 4, we will find the characters dealing with the repercussions of a world overcome with Promicin use. So, we built a bridge in the story that would generate excitement for the season premiere without divulging too much of the new season’s plotline.Another method of expanding a storyworld but managing point-of-entry is to switch to another point of view. The online augmentations to Cloverfield (Paramount Pictures, 2008) were an attempt to provide information anterior to the events in the film, from the point of view of different characters. Pertinent events related to the mystery of the 'monster' could not be revealed by any of the characters in the film, since they were not aware of it before-hand. In an interview conducted by Silas Lesnick (2007), the director of Cloverfield, Matt Reeves, spoke about the relationship between the feature film and online augmentations:

You can experience it that way or, if you so wish - I guess that's the thing; what was exciting about the idea of doing this handicam movie was the idea of point of view. How we were rooted in this point of view and there were places where the camera can't get in. [...] We thought what would be really interesting, even just thinking about the idea that this event could be seen from a different person. This is what happened when this event happened to these people. But there's actually another idea, another movie, another point of view, another prism to look through to what other people - who else might being going through the same experience. In a way, the internet sort of stories and connections and clues are, in a way, a prism and they're another way of looking at the same thing. To us, it's just another exciting aspect of the storytelling.The online augmentations are not substantial enough (at this stage) to be regarded as an ARG (it isn't a 'work' in itself), but they do supply critical information that the film does not. Reeves in Lesnick (2007) describes their approach not as 'tangential' but as (appropriately) tentacles:

It's [www.slusho.jp] a connection, obviously, back to a reference to Alias and it's part of the involved connectivity between that and there's a - I don't know what you could call it - a sort of “meta-story” that is part of - almost like an origin story - that is connected. It's almost like tentacles that grow out of the film and lead, also, to the ideas in the film. And there's this weird way where you can go see the movie and it's one experience. [...] But there's also this other place where you can get engaged where there's this other sort of aspect for all those people who are into that. [...] All the stories kind of bounce off one another and inform each other. But, at the end of the day, this movie stands on it's own to be a movie.

Figure 4. Close-up screenshot from Cloverfield 'Kishin' manga comic |

Do I imagine that that those of you participating in Eldritch Errors right now might be among those who buy a graphic novel, or tune into a television show, or buy the DVD of a movie? Yes, but you are more the stars of the product and the collaborators in that story development behind it, with the product intended for graphic novel buyers and television show viewers and DVD purchasers.One could argue that the numbers of ARG players when compared to cinema attendences or even DVD buyers are insignificant, and so satisfying their needs are secondary. Though this thinking may inform some design decisions, it elides many truths: such as their highly vocal and pervasive online presence, and the fact that many of the players are also fans (or potential fans) of the traditional entertainment property. A more significant issue, however, is that most creators of the traditional media properties are not skilled in expressing across artforms. So, even if they did or do value players, they cannot satisfy their needs and (perhaps unconsciously) regard an ARG as exterior to the main work, not at all equal to it.

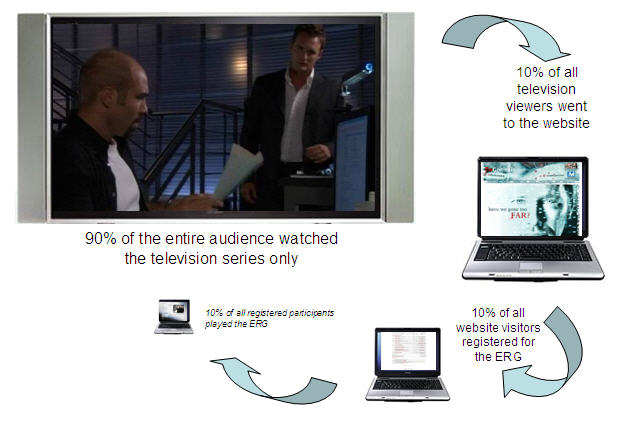

The show is a tool for the game, but is in no way necessary. It sometimes provides clues and hints about what to do next in the ARG- but these clues are usually posted within minutes on the in-game forums. That being said, by not watching the show, you miss out on a lot of the character development, and some of the minor plot developments. Keeping all this in mind, you'll still have fun with or without the show. I know there were players last time who did just as much if not more then the people who were watching the show.Before I discuss how the designers engineered this tiered approach, I’ll outline the various components created by the producers (Shaftesbury Films & Xenophile Media): television series; podcast that is a recap of the show and the ERG; podcast of the music in the series (ReGenesis: ReMixed); show forum (ReGenesis.tv); Extended Reality Game (including many sites). An audience member could experience all of these in a range of combinations. Indeed, the possible combinations of these five components in the ReGenesis II property provide one-hundred and fifty-three possible paths. For instance, one could watch the show only, or the show and music podcast only and so on. Assessed according to the components that define the storyworld, ReGenesis II has three primary tiers:

Figure 5. Audience movement from TV show to ERG |

The work level refers to separate content within a single work (single ARG), content that is designed to appeal to different players and audiences.

To ‘play’ an ARG, therefore,

is not necessarily to engage in homogenous content supplied by the initial producers. ARGs are tiered by their creators, but players also create

other tiers. So the boundary of the 'work' of an ARG is not defined by any single producer. Examples of 'work' tiering are

offered in the Tier Types section.

The last kind of game includes those which are based on the pursuit of vertigo and which consist of an attempt to momentarily destroy the stability of perception and inflict a kind of volumptuous panic upon an otherwise ludic mind. In all cases, it is a question of surrendering to a kind of spasm, seizure, or shock which destroys reality with sovereign brusqueness.Although the ARG player doesn't experience such vertigo physically, and it does not have to be a state of 'panic', it is the 'shock' of discovering something that operates in a wholly different fashion that was appealing to many. As many designers and players have said, it is the experience of seeing things differently and having to figure out what the game is (which cannot be facilitated as readily when employing the same gameplay design) that made The Beast so appealing. ARG designer Dave Szulborski (2005a, pp.58) explains this definition of ARGs:

[A]n alternate reality game can be said to have rules but they aren’t defined and written out anywhere. Instead, the player learns these rules through his observation of and interaction with the game. In this way, alternate reality games are a very special form of game, shedding the restrictive concept of defined rules and taking on more of the appearance of true play.ARG designers do try to perpetuate this reinvention of the game approach without completely altering the rules by not varying the mediums used. This quote from the Chief Creative Officer of 42 Entertainment, Alex Leiu (2007), reveals this approach:

Any platform that you can give us that we can put in front of you and have it personally touch your lives and go 'Wow! That was amazing! I never would of thought that I could of walked into a bathroom and picked up a USB drive and got the latest Nine Inch Nails song.' I think that's what makes us unique. [...] There's so much in the world. When we talk about the world as a platform, there are so many things you guys come across every single day and don't even give it a second look. And one of the things we do is make you give it a second look and actually have a world explode from that.Indeed ARG designer Elan Lee (2006) -- who was the co-founder of 42 Entertainment and now co-founder of Fourth Wall Studios -- defines an ARG by this reconfiguration of non-entertainment objects:

An alternate reality game is anything that takes your life and converts it into an entertainment space.

Created: 24 Sep, 2007

Last Updated: 25 March, 2008

Author: Christy Dena